FEATURE STORY

The Day Norman Mailer Came to Class

By Ty DeMartino '90

The memory was hazy, at first. But then it became clearer.

Yes, the man sitting in the back of Barbara Graves’s ’66 8 a.m. English class on that brisk Frostburg morning, was, indeed, prolific American novelist Norman Mailer.

Wait. What?

Barbara Graves '66

“Yes, he sat there like everyone else,” Graves recalled. “And he participated in the discussion about his own book that we were going to read.”

Okay. Let’s back up.

By the early 1960s, Mailer had already gained fame for his 1948 novel “The Naked and the Dead” and would later go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction for “The Armies of the Night.” Mailer also gained fame as a journalist, playwright, controversial speaker, aspiring politician and perpetual curmudgeon. He was as controversial for his outspokenness as he was talented.

Mailer’s Frostburg connection can be traced back to Graves’s Frostburg English professor, Edmund Skellings. She remembers Skellings was an “avant-garde” instructor who marched to the beat of his own drum. While other male professors wore the required suit and tie to class, Skellings donned a crewneck sweater and blazer and sat cross-legged on his desk. Two unconventional habits that were frowned upon by the administration, Graves recalled.

“[Skellings] was very informal. He wanted to create a relationship with his students,” said Graves, a retired educator. “I see now that it was all about engagement.”

And what better way to engage his students than to casually bring a world-famous author to class?

Prior to Frostburg, Skellings received his doctorate in British and American literature at the University of Iowa where he was involved with the school’s Writer’s Workshop. Graves believes this is where Skellings must have forged a friendship with Mailer and later invited him to visit Frostburg to sit in on his early morning English class.

FSU English professor Edmund Skellings

“[Skellings] said, ‘I’d like to introduce my friend, Norman. He’s here to join in our discussion today,’” Graves recalled, and admitted Mailer’s presence was completely “lost” on her. “Maybe if it was John Steinbeck or Hemmingway, I would have recognized him.”

Graves didn’t get true perspective on her brush with literary greatness until years later. A quick Google search by Graves revealed that there was indeed a connection between the two men, including correspondence between Mailer and Skellings that spanned five decades. Several of their letters are archived with Project: Mailer, the Digital Humanities Initiative of the Norman Mailer Society and on the campus of the Florida Institute of Technology.

Mailer, of course, was considered a pioneer of “creative fiction,” alongside greats as Truman Capote and Hunter S. Thompson. Before his death in 2007, he wrote eleven best-selling novels and was known for his often-controversial appearances on talk shows which later inspired one Frostburg student to drop out of school and pursue a career as a writer in New York City (see sidebar).

Skellings only taught at Frostburg for a few years before he packed up his crew neck sweaters and moved on to the University of Alaska. He eventually settled in Florida where he gained fame as a ground-breaking poet and artist blending the written word with sound and technology, earning him the nickname “the electric poet.” With seven books written, Skellings was named Poet Laureate of the state of Florida for 32 years. He passed away in 2012.

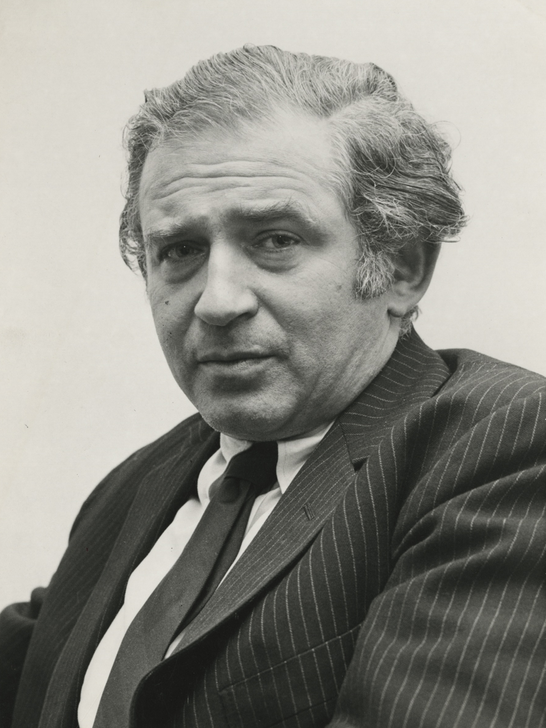

Norman Mailer

As for Graves, she only has fond memories of Skellings. “He taught me a lot about writing.”

She’s tickled looking back at her brush with Mailer, even though she and the other students didn’t fully realize it at the time.

“He just sat there. And no one knew.”