Garrett County By Location

Accident. According to local tradition, the town’s name springs from two accidents: first, the overlapping claims of surveyors Brooke Beall and William Deakins Jr. circa 1786; second, the “accident” being duly recorded in the official documents as the place name. See “Town Named Accident.” Roadside America. Updated 16 Aug. 2020. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/49084

Accident. Mary Shoemaker Beitzel, who died in 1930 at age 88, must have made quite an impression in life, because news of her death was supernaturally communicated via a "token" in two different households, in two different ways: as an apparition standing over her great-nephew's bedside, and as a mysterious, sourceless buzzing in her grandson's kitchen cupboard, like an invisible bee. Granma Mary's epitaph in St. Paul's "New" Cemetery: "There is rest in heaven." See Duncan, Andy. "She Recognized the Old Lady in the Coffin." Weird Western Maryland. 12 Nov. 2021. https://weirdwesternmd.blogspot.com/2021/11/she-recognized-old-lady-in-coffin.html . Also Duncan, Andy. "Ask Not for Whom the Bee Buzzes." Weird Western Maryland. 13 Nov. 2021. https://weirdwesternmd.blogspot.com/2021/11/ask-not-for-whom-bee-buzzes.html. The Find a Grave entry is https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/61887429/mary-elizabeth-beitzel.

Avilton. In January 2009, two nighttime travelers in a moving car saw in the sky a “long strand of equally spaced red lights” that looked “very large and unexplainable.” Today, this would be dismissed as beacons atop the turbines along the ridge near Savage River Lodge--but that wind farm didn’t switch on until 2015. Maybe the travelers saw the Meyersdale, Pennsylvania, wind farm, 15 miles north and operating since 2003. See “Sighting Report 1/31/2009, Avilton (Frostburg) MD.” National UFO Reporting Center (NUFORC). https://nuforc.org/sighting/?id=68409

Bittinger. Photos of a beagle and a fawn sharing a sofa went viral after being named the July 2008 Photo of the Month by the Deep Creek Times. Supposedly the fawn had followed its newfound friend through the pet door; Snopes.com suspected “a staged scene with a tame deer.” See David Mikkelson, “A Beagle and a Fawn.” Snopes.com. 29 Jan. 2014. https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/beagle-and-fawn/

Bloomington. The long-gone three-story Italianate brick house known as Borderside, a.k.a. the Brydon Mansion, built c. 1870, sat on five acres at Maryland Highway (Route 135) and North Branch Avenue, roughly where the WEPCO Federal Credit Union sits now. It merits mention on this page because of this curious 1984 reference: “In the vicinity of the razed mansion … the archeologist will find a rock formation bearing the tracks of a prehistoric animal.” Does anyone know anything more about this fossil? See Kenny, Hamill. The Place Names of Maryland: Their Origin and Meaning. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984. Second printing, 1999. Page 44.

Bloomington. Just outside Luke, Highway 135 down Backbone Mountain bottoms out abruptly in a 90-degree turn at a stone face painted with white crosses, one for each of the scores of people killed in wrecks there. See “Deadly Curve of Crosses.” Roadside America. Rev. 8 Sept. 2012. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/35454

Deep Creek Lake. Buffalo Marsh was named for a corpse: “The first white settlers found the carcass of a large buffalo in this marsh.” Flooded when Deep Creek Lake was created, the marsh is now the cove on which sits the Lake Pointe Inn, where accommodations include a Buffalo Marsh Suite. See https://deepcreekinns.com/history/, https://deepcreekinns.com/buffalo-marsh-suite/ and Kenny, Hamill. The Place Names of Maryland: Their Origin and Meaning. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984. Second printing, 1999. Page 49.

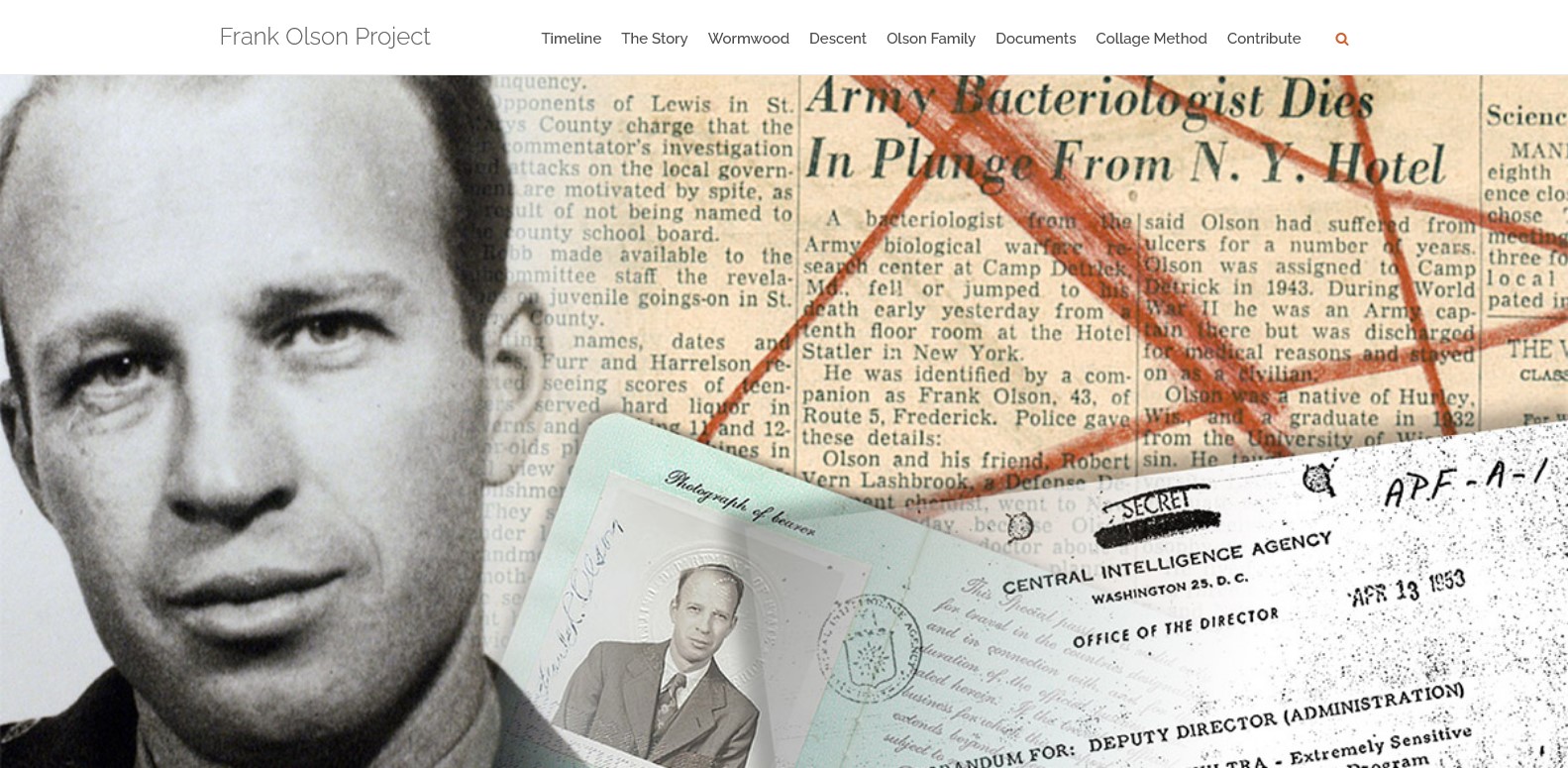

Deep Creek Lake. Decades later, President Ford would apologize in the Oval Office to the family of Fort Detrick biologist Frank Olson, who fell to his death on a Manhattan sidewalk from a high-rise hotel window on Thanksgiving weekend 1953—only 10 days after he had been unwittingly dosed with LSD at a Deep Creek Lake rental cabin by CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb, responsible for the infamous “brainwashing” project MK-Ultra. Whether Olson’s death was suicide or murder, and the implications of either, form Western Maryland’s most disturbing set of conspiracy theories. See son Eric Olson’s Frank Olson Project at https://frankolsonproject.com/ and director Errol Morris’s 2017 Netflix docudrama Wormwood at https://www.netflix.com/title/80059446 .

Deep Creek Lake. In the 1990s, when the now-closed-for-renovations Inn at Deep Creek (https://www.innatdeepcreek.com/ ) was known as the Alpine Village Inn, the proprietors claimed the ghosts of Native Americans haunted the grounds and an (unnamed) nearby restaurant claimed the apparition of an "Indian chief," says author Amelia Cotter, who stayed at the inn with her family as a kid. "There was even a leaflet included in the restaurant's menu to educate, or warn, guests about the chief's regular appearances," recalls Cotter. We'd love to see that menu and that insert! At the inn, Cotter's family was rudely awakened at 5 a.m., she says, by an unseen force yanking open the door of their fridge and dumping its contents to the floor. See Cotter, Amelia. Maryland Ghosts: Paranormal Encounters in the Free State. Black Oak Media, 2012. Haunted Road Media, 2015. Kindle edition. Pages 29-32.

Deep Creek Lake. University of Virginia researchers believe that classic "crisis apparitions"--the sudden, spectral appearances of distant loved ones as a tipoff of calamity--"may be just as common now as they were 100 years ago, although we rarely hear about them." One 20th-century example is also a Christmas ghost story: A man who drowned with two others in Deep Creek Lake when his new snowmobile broke through the ice appeared to his wife, "shivering all over and drenched to the bone," moments before the police arrived with the terrible news. Can anyone find a contemporary account of this fatality, with names, dates and locations? See Coleman, Dorcas. "Spooky Stuff in State Parks." The Natural Resource Magazine. Fall 2001. Posted in October 2016 at https://dnr.maryland.gov/Pages/Spooky-State-Parks.aspx. See also Okonowicz, Ed. "Deep Creek Tragedy." In The Big Book of Maryland Ghost Stories (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2010): 331-333.

Grantsville. When voters ratified the creation of Garrett County in the November 4, 1872, general election, they chose Oakland over Grantsville by only 63 votes. One wonders whether local opposition to President Ulysses S. Grant was a factor: Maryland was one of only six states carried that year by Grant’s Democratic opponent, New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley. Already grief-stricken over his wife’s death in October, Greeley retreated to a Pleasantville, New York, mental institution, where he died 24 days after the election, age 61. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 7; Wikipedia, “1872 United States presidential election,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1872_United_States_presidential_election; Wikipedia, “Horace Greeley,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horace_Greeley.

Grantsville. During a long weekend in summer 1964 in a rented four-room cabin, a 14-year-old girl and her sister briefly saw the apparition of "an elderly man who was slowly stroking the head of our dog." The cabin was surrounded by the graves of the previous owner's beloved dogs, each marked with a hand-carved stone. Can anyone help identify the cabin and/or its dog-loving owner? See Okonowicz, Ed. "Dog's Best Friend." In The Big Book of Maryland Ghost Stories (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2010): 329-331.

Long Stretch. A Shades of Death Road in New Jersey has become infamous, but Garrett County once had its own, so named in colonial times because of "the dense gloom of the summer woods, and the favorable shelter which these enormous [white] pines would give an ... enemy," wrote J. Thomas Scharf in 1882, placing the grove north of the National Road and west of Savage Mountain. A twentieth-century writer got carried away: "No bird chirps among the foliage or finds food in these inhospitable boughs ... at every step the traveler half looks to find a bloody corpse or the blanched skeleton of some long murdered man lying across the pathway through these woods." This appears on the historical marker outside the Hen House restaurant, on a famous straightaway through farmland that no longer seems scary at all. See Jones, Devry Becker. "The Long Stretch." The Historical Marker Database. 26 May 2019. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=134376. See also Scharf, J. Thomas. History of Western Maryland. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts, 1882. Accessed via the Internet Archive. See also Stegmaier, Harry Jr., David Dean, Gordon Kershaw and John Wiseman. Allegany County: A History. Cumberland, Maryland: Allegany County Commissioners, 1976; printed by McClain Printing in Parsons, West Virginia; second printing 1983. Page 42.

Long Stretch. This famous straightaway, home of the Hen House restaurant and Route 40 Elementary School, was in September 2015 the location of a 20-minute sighting, by a parent and an 8-year-old, of “a bright yellow arch seen at an oblique angle, probably reflecting the setting sun,” that over time “totally changed shape and color. With the naked eye, it was just a bright orangeish light. With the binoculars, it looked like a dark oblong object in a horizontal position with a bright reddish light at the center base.” A passer-by saw the same thing: a reflective sundog, possibly, though it seemed to be “coming slightly toward us and moving to our left.” See “Sighting Report 9/17/2015, Frostburg, MD.” National UFO Reporting Center (NUFORC). https://nuforc.org/sighting/?id=122182

Meadow Mountain. “West of Frostburg, at the foot of Meadow Mountain, a Union soldier was reputedly brutally murdered in a home where he had taken lodging. When he tried to escape he left the bloody print of his hand on the heavy wooden paneling of the front door. Despite all attempts to remove it, the stain remained there as clear as the night it had been left, until the house burned after the turn of the century” -- that is, circa 1900. The legend of the “ineradicable bloodstain” is said to be nearly “ubiquitous” in Maryland. See Carey, George G. Maryland Folklore and Folklife. Centreville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1970; fourth printing, 1983. Pages 32-33.

Monkey Lodge Hill. How this 2,700-foot summit near Bittinger got its name is anyone’s guess, but it must have been long ago, as the name was in Gannett’s Gazetteer of Maryland in 1904. Toponymist Hamill Kenny suggested the hill boasted “monkey trees” good for climbing, but conceded: “The name has not been solved.” Today the hill is the site and namesake of a luxury vacation rental (https://redbarnvacations.com/monkey-lodge-hill/). See Kenny, Hamill. The Place Names of Maryland: Their Origin and Meaning. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984. Second printing, 1999. Page 160.

Muddy Creek. “The creek which flows forth from the Cranesville Swamp is clear and sparkling and completely belies its name.” See Kenny, Hamill. The Place Names of Maryland: Their Origin and Meaning. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1984. Second printing, 1999. Page 167.

Oakland. Early 19th-century land patents often had whimsical names; the Oakland-area patent was named The Wilderness Shall Smile. The town name “Oakland” was suggested by the founder’s daughter—whose own name, interestingly, was Ingabe McCarty. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 9.

Oakland. Originally nicknamed “the stone church,” the 1869 building that long has housed St. Matthew’s Episcopal is better known as “the Church of the Presidents,” because it was visited by four U.S. presidents of the Gilded Age: Ulysses S. Grant (POTUS #18), James A. Garfield (#20), Benjamin Harrison (#23) and Grover Cleveland (#22 & #24). This attests to the area’s reputation as a swank resort for the privileged and to the political connections built by B&O Railroad magnate John Work Garrett, the county’s namesake. See Prats, J.J. “Garrett Memorial Church.” The Historical Marker Database. 30 July 2006. Last updated 29 September 2023. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=467

Oakland. When voters ratified the creation of Garrett County in the November 4, 1872, general election, they chose Oakland over Grantsville by only 63 votes. For more, see Grantsville. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 7.

Oakland. The roof and walls around Washington Spring date from the 1875 construction of the otherwise long-gone Oakland Hotel, whose publicists may have invented the “tradition” that George Washington drank (water) there. A 1900 tourist guide put it best: “It never has been successfully denied that Gen. George Washington did not drink of this spring.” See Browne, Allen C. “Tradition of Washington Spring.” The Historical Marker Database. 25 September 2013. Last updated 18 July 2020. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=68806

Oakland. The first telephone line in Garrett County was installed in 1883 by Alexander Graham Bell himself. It connected two palatial resort hotels owned by the B&O Railroad: the Oakland Hotel and the Deer Park Hotel, both long gone. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 31.

Oakland. When voters rejected a bond issue to build a new school, the county built one anyway, at the corner of Centre and Wilson streets. Upon completion in 1894, it had cost $12,512.45, about $465,000 in today’s dollars—a bargain price that left almost nothing in the coffers to pay teachers. As a result, that year’s school term lasted only six weeks. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 21.

Oakland. The original Garrett County Jail, built in 1913 and demolished in the late 1970s, had crenellated stone walls and looked like a medieval castle. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 13.

Oakland. The handwriting on a postcard from Oakland, dated November 16, 1920: “Hello Cara. We got here OK. Was two hours and forty minutes coming. Never changed gears. All was well. Didn’t get a bit cold. Stephen.” See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 34.

Oakland. In 1949, for Oakland’s sesquicentennial—that is, 150th anniversary—a giant birthday cake was built on the courthouse lawn. “The cake took three weeks to build, stood over 12 feet high, and consisted of 700 feet of lumber, 250 feet of chicken wire, a ton of newspaper for papier-mache, and 25 gallons of paint.” It was quite inedible. See Feldstein, Albert L. Garrett County. Postcard History Series. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2006. Page 14.

Oakland. Rotary Park has a detailed historical marker about the Chesapeake Bay watershed, informative but unfortunately placed: Western Garrett County, Oakland included, is west of the Eastern Continental Divide and therefore the only part of Maryland that does not drain into the bay. It drains ultimately into the Gulf of Mexico instead. Local wits say that Garrett Countians are so Republican that they deny Baltimore even their runoff. See “MaryLandscapes.” The Historical Marker Database. 17 Aug. 2006; rev. 14 July 2019. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=486

Redhouse. As Garrett County wind chills reached minus 40 in December 1993, the state Department of Natural Resources received more than 100 calls about migrating loons trapped in pond ice. On Wednesday, Dec. 29, a 38-year-old DNR employee attempted a solo rescue of a loon in a farm pond on U.S. 50, but his canoe overturned before he could reach the bird, and he was in the frigid water for 30 minutes before a passer-by pulled him out. He died in the hospital that night. The employee who sacrificed himself for a loon was not a park ranger but a mechanic; because of the holiday, he was the only person in the Mount Nebo office when the call came in. See Sterling, TaNoah V. “Wildlife worker dies trying to save bird.” The Baltimore Sun. 2 Jan. 1994. Page 6B. Accessed via Ort Library’s ProQuest newspaper database.